It’s a Wanda-ful life

30.06.2015 WANG JIANLIN started life with a red spoon in his mouth. His father was a Communist military hero who fought alongside Mao. Thanks to his influence, the youngster was able to join the People’s Liberation Army at 15 and so avoid the worst deprivations of the Cultural Revolution.

WANG JIANLIN started life with a red spoon in his mouth. His father was a Communist military hero who fought alongside Mao. Thanks to his influence, the youngster was able to join the People’s Liberation Army at 15 and so avoid the worst deprivations of the Cultural Revolution.

After 17 years in the army, he decided that the future belonged not to generals but to businessmen. So in 1988, after a stint as a bureaucrat, he formed a property company in the north-eastern city of Dalian, using $80,000 of borrowed money.

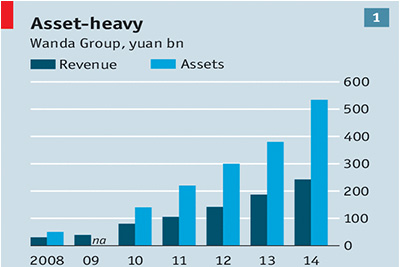

His firm, Dalian Wanda, is now China’s biggest private property developer, with shopping centres opened, or coming soon, in 100 cities. Last year its revenues rose to 243 billion yuan ($40 billion), up by 30% on a year earlier (see chart 1). The $3.7 billion flotation of its property division in December sent his personal fortune soaring past $25 billion: he vies with Alibaba’s Jack Ma for the title of the country’s richest man. Now China’s land king is going global and diversifying from property.

He is doing so in style. You do not expect blaring disco music and strobes, leggy beauties and champagne first thing in the morning. But that is how Mr Wang—who favours private jets and flashy yachts (he owns Sunseeker, the British maker of the sleek craft seen in James Bond films)—celebrated his latest deal on February 10th. In the glittering ballroom of the Sofitel Wanda hotel in Beijing, he toasted a $1.2 billion deal to buy InFront Sports & Media, which holds some of the marketing rights to FIFA’s World Cup. The previous month he took a 20% stake in Atlético Madrid football club. Mr Wang is also on track to become the world’s biggest owner of five-star hotels, with billion-dollar investments in Sydney, London, Chicago and Los Angeles.

Hollywood moguls were perplexed when some Asian guy they hadn’t heard of bought AMC, a big but struggling American cinema chain, for $2.6 billion in 2012. Some scoffed at his plans to spend $8 billion on the world’s largest studio complex in Qingdao, China. But they certainly took note when he got Leonardo DiCaprio, John Travolta, Kate Beckinsale and other celebrities to fly there for the project’s launch in 2013. He is now rumoured to have Lionsgate, the studio behind “The Hunger Games”, in his sights.

Out-Disneying Disney

Mr Wang wants to transform Dalian Wanda into a global entertainment colossus capable of beating Disney, which plans to open Shanghai Disneyland next year. He is dreaming up acquisitions that will increase his group’s annual revenues by 2020 to $100 billion, a fifth to come from outside China. He insists it can become a global force like Google and Walmart.

Mr Wang is clearly a man of Napoleonic ambition. The influence of his years in the PLA, where he rose from border guard to regimental commander, is evident. He is now 60 but maintains a trim figure and erect bearing. He also insists on iron discipline at work. Employees are fined for violating his conservative dress code.

However, his charmed career and his free-spending ways raise several important questions about Dalian Wanda’s future. Could the cash cows funding his spending spree—those giant shopping centres—run dry as Chinese consumers switch to buying online? Does his diversification into ego-stroking industries make business sense? And will the close ties with government that have served him well thus far prove a liability in future?

Take the threat to his core property business first, where Wanda’s bricks-and-mortar empire faces the twin dangers of a weak property market and rising online competition. China is experiencing a tidal wave of retail development. Jones Lang LaSalle, a property-management firm, estimates that the total floorspace at shopping malls in the biggest 20 cities will rise from 62m square metres now to 87m in two years. On top of the risk of oversupply, the value of the land on which developers’ loans are secured is falling. Both problems are worse in the country’s secondary cities.

Yet Wanda’s prospects look strong. One analyst who studies the group thinks its strategy of building malls only in the heart of secondary cities, compared with that of rivals who chose (or were stuck with) cheaper plots on the periphery, means that “the oversupply issue is less relevant to Wanda.” Oscar Choi, an analyst at Citigroup, has visited Wanda Plaza malls in cities large and small; he was impressed by how efficiently they were run, and their pulling-power among local consumers.

All this is helping the group with its defences against the spread of e-commerce, which is hitting many Chinese shops hard. In August it launched a 5 billion yuan venture with Baidu and Tencent, two leading internet firms, to devise “online to offline” services, in which consumers use their smartphones to choose products but are then led to a physical shop, where they buy them. It also recently bought 99 Bill, a local online-payments firm.

As part of this plan, Wanda is now wiring up all of its shopping centres with Wi-Fi and Bluetooth sensors so that shoppers can be monitored intensely. A new app, to be launched soon, will ping them with promotions and information as they step inside the malls, and will let them do such things as book parking spaces. Consumers can peruse goods on the shelves but pay on their mobile phones to save queuing, and have their goods delivered straight to their homes.

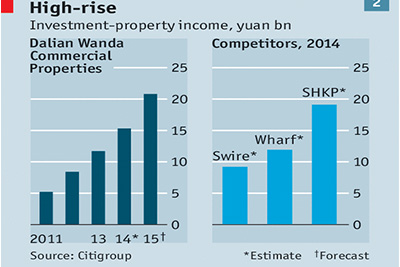

Citigroup predicts that net profits at the firm’s property division will keep soaring, rising by over half between 2014 and 2016, to 22.8 billion yuan. Wanda’s malls have remarkably high occupancy rates. The firm also compares favourably to its rivals on the income generated by its investment properties, which looks set to rise to 21 billion yuan this year, up by a third on last year (see chart 2).

Studies show that the types of product most affected by e-commerce are those that Mr Wang calls “shopping-basket goods”: clothes, accessories, electronics and the like. He acknowledges that sales of these sorts of things are suffering at his centres. To offset this, he is expanding his plazas’ offerings in “experiential consumption”: karaoke bars, cultural shows and other things that cannot be enjoyed on Alibaba. Wanda has done more than its rivals to shift its malls’ mix of tenants in this direction. Now, tenants offering such services occupy about 40% of its floor space, which is to rise to 60% over time.

Studies show that the types of product most affected by e-commerce are those that Mr Wang calls “shopping-basket goods”: clothes, accessories, electronics and the like. He acknowledges that sales of these sorts of things are suffering at his centres. To offset this, he is expanding his plazas’ offerings in “experiential consumption”: karaoke bars, cultural shows and other things that cannot be enjoyed on Alibaba. Wanda has done more than its rivals to shift its malls’ mix of tenants in this direction. Now, tenants offering such services occupy about 40% of its floor space, which is to rise to 60% over time.

His diversification into theme parks, film-making and other entertainment services follows a similar logic. As the country’s investment-driven model of growth gives way to one focused on consumption, the services sector seems certain to rise. The Chinese government is keen to encourage the rise of strong domestic companies in this area, and as it happens Mr Wang is the best-connected businessman in the country.

That leads to the most important question: what does Mr Wang’s close relationship with high officialdom mean for the future of Dalian Wanda? He is a long-standing member of the Communist Party, and has served as a deputy to its National Congress. CCTV, the main state television network, has named him its “Economic Person of the Year” not once but twice.

Given his firm’s operational know-how and its sensible diversification strategy, it would be wrong to dismiss him as just another Asian crony capitalist living off his connections. Even so, these political ties warrant scrutiny. Do they in any way help to explain h